Divorce has long been recognised as a complex, often heart-wrenching process. When it involves shared property, finances, and matters of custody, the division can become intricate. But the emergence of modern reproductive technologies has added another emotionally charged layer: what happens to fertilised embryos, stored sperm or eggs, and other fertility-related assets? These biological resources represent not only scientific advancement but for many, the promise—or memory—of a family. As couples undergoing fertility treatments increasingly face relationship breakdowns, courts are being asked to adjudicate on questions that pit personal autonomy, ethics, and contracts against deeply intimate issues of parenthood.

Reproductive Technology in the Modern Age

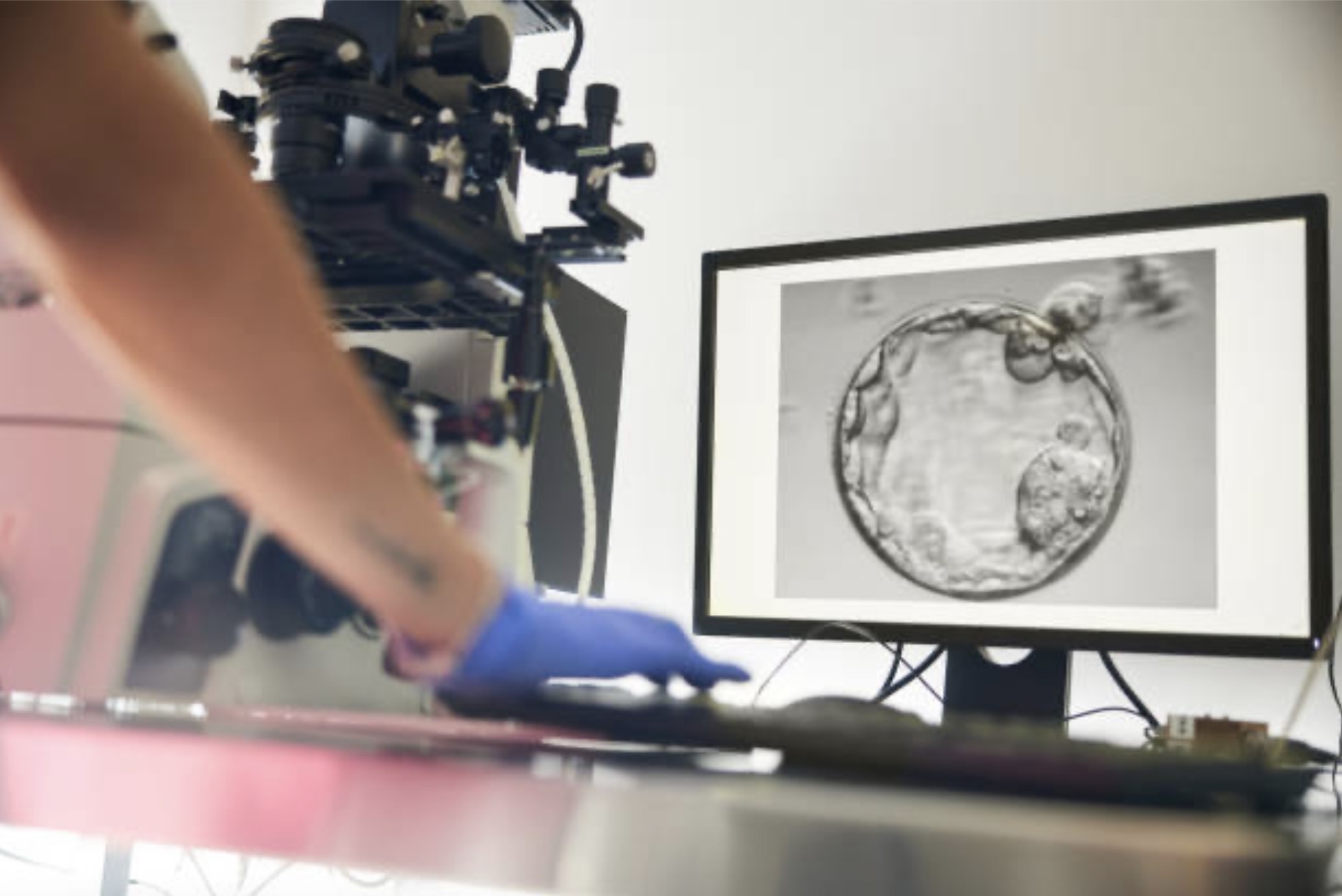

Over the past few decades, assisted reproductive technologies (ART), including in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and embryo cryopreservation, have revolutionised how people build families. Individuals and couples routinely deposit eggs, sperm, and embryos into long-term storage with fertility clinics. These assets are essentially frozen snapshots of reproductive potential, often created during a more hopeful chapter in a couple’s journey.

In many cases, couples decide to freeze embryos after undergoing arduous, expensive procedures—and often with the clear intention to use them to start or expand a family. However, when the relationship falters before the embryos are used, it leads to a difficult question: who has the right to decide what happens to shared future potential children?

Legal Precedent and Frameworks

Unlike traditional property, embryos occupy a unique legal space. They are not mere biological material, nor are they legally classified as children. They straddle an ambiguous middle ground, which makes legal determinations particularly complicated. The UK, as well as many jurisdictions worldwide, haven’t developed comprehensive statutes that easily fit these specific circumstances, so courts often resort to interpreting pre-existing contracts and applying broader principles of family law and human rights.

In the UK, embryos can only be created, stored, and transferred under strict licensing from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). One standard requirement before treatment begins is that both partners provide written, informed consent for every aspect of the embryo’s creation, storage, and potential future use. Crucially, this consent must be ongoing. A person can withdraw consent at any point before embryo transfer, which makes mutual agreement essential at every stage.

The landmark case of Natallie Evans in the mid-2000s illustrated how decisive this principle could be. Ms Evans lost her fertility following cancer treatment and had frozen embryos created with her then-partner beforehand. After the relationship ended, her ex-partner withdrew consent for their use. Despite emotional and reproductive consequences for Evans, several courts, including the European Court of Human Rights, upheld his right to withdraw consent, citing his reproductive autonomy. The embryos were eventually destroyed.

This case set a firm precedent that no one can be forced into genetic parenthood against their will. Yet while the ruling provided a legal framework, it did little to ease the emotional and moral dilemma many couples experience when their fertility assets outlast their romantic relationship.

The Role of Consent and Contract Law

Much of what governs the fate of embryos in divorce hinges on consent, as signed before treatment. Fertility clinics usually include detailed consent forms in compliance with HFEA regulations. These forms ask pertinent questions: can one person use the embryos if the other dies? What happens if the couple splits? For how long can the embryos remain in storage?

Although these documents are legally binding to a point, contract law alone does not fully address all ethical dimensions, particularly when circumstances change over time—such as a divorce years into what was once a unified parental plan. Courts may still be required to interpret contracts within the broader scope of individual rights, morality, and fairness.

Moreover, not all agreements are drafted with divorce in mind. What seems like a formality during therapy may prove crucial during litigation. Discrepancies in interpretation or failure to update consents after relationship changes may expose couples to long legal battles.

In a few contentious cases, former partners have attempted to argue for embryo use under claims akin to “specific performance” of a contract, or under the Human Rights Act, particularly Article 8—the right to respect for private and family life. However, UK courts have so far consistently rejected claims that one person’s desire to become a parent outweighs another’s wish not to.

International Divergence in Legal Outcomes

The legal landscape elsewhere is equally patchy and varies greatly across jurisdictions. In the United States, for example, different states handle frozen embryos differently depending on whether they view them as property, something more akin to children, or a unique category deserving of special treatment.

Some US courts have favoured the party opposing use, upholding mutual consent as a requirement. Others have awarded custody of embryos to the party with no other means of biological parenthood, recognising reproductive rights and the potential emotional damage of losing their last chance to become a genetic parent.

In contrast to the UK, some countries, like Israel, have shown greater willingness to view embryos through a familial or moral lens. Courts there have occasionally erred on the side of allowing use, especially in cases involving widows or singular motherhood where future parenting opportunities are not easily duplicable.

This divergence underscores how cultural, religious and ethical differences shape legal interpretation. For couples with international ties—or for those who may have stored fertility materials abroad—the law becomes an even more complex maze.

The Emotional Landscape

Beneath the legalese lies a realm of deep emotion. Embryos created during IVF often represent hope after years of fertility struggles. When a relationship ends, decisions about these embryos are not merely administrative—they’re profoundly personal. One partner may cling to the embryos as their sole chance at genetic parenthood. Another may be unwilling to allow the possibility of becoming a parent with someone they no longer love or trust.

These issues are intensely emotional not because they involve rights alone, but repercussions that can redefine the rest of someone’s life. There is also the challenge of grief—letting go not only of a relationship, but possibly of a dream one built through years of physical, emotional and financial investment.

Fertility counselling is strongly recommended during IVF treatment, especially for prospective parents facing ambiguous or difficult choices. In ideal scenarios, clinics also offer post-separation counselling, though access can be limited, and emotions are often raw. Unfortunately, people rarely anticipate needing such support until the crisis has surfaced.

Alternatives and Outcomes

When mutual agreement cannot be reached and one party revokes consent, the default in UK law is straightforward: the embryos cannot be used and must eventually be destroyed. This outcome can feel unacceptably harsh to someone for whom this represented their last hope of having genetically linked children. However, to compel someone into parenthood—however passive their role may be—is a breach of their autonomy.

Where mutual consent remains intact, even during separation or divorce (which is rare but not impossible), the embryos may still be used by one party. In such cases, courts may step in to clarify parental responsibilities and financial obligations, particularly if resulting children are born from this arrangement.

Another option increasingly considered is donation. Some people decide to donate embryos to medical research or to other infertile couples once the relationship ends. While complicated, donation can offer a sense of purpose following a difficult split—but it also comes with risks, including knowing that a biological child may exist in the world without their direct involvement.

Given these delicate options, some couples preemptively choose to discard or donate unused embryos after a break-up to avoid prolonged legal or emotional strain.

Proactive Planning and Legal Advice

The looming possibility of relationship breakdown is not easily talked about during fertility treatments. But more fertility clinics are encouraging clients to seriously consider future scenarios, including conflict and separation. Legal reforms might eventually mandate more specific consent agreements, or periodic reviews of ongoing consent to better reflect changing relational dynamics.

Seeking independent legal advice before or during the fertility process is another prudent step. While previously rare, it is becoming more common for family lawyers to guide clients not only through property or custody decisions, but also through complex bioethical matters like fertility preservation and disposal rights. This growing specialism ensures that individuals can make reflective, informed decisions that hold up legally and emotionally.

Future Legal and Ethical Considerations

As reproductive technologies continue to evolve, so too do the ethical conundrums surrounding them. New advances like artificial wombs, gene editing, and the growing emphasis on reproductive autonomy invite legal reform and societal discussion.

Debates around stored embryos are unlikely to wane. Instead, they will intensify as more people delay parenthood, face infertility, or choose non-traditional paths to family creation. Legislators will be pushed to design more nuanced policies balancing bodily autonomy with reproductive rights, possibly introducing conditional consent scenarios, better definitions of “reproductive property,” or updated statutory protections for those whose fertility windows do not align with their relational timelines.

Meanwhile, courts will need to develop a more harmonised framework for precedent, as different decisions based on similar facts continue to create uncertainty.

Conclusion

The dissolution of a relationship is never easy. But when that ending holds the fate of frozen embryos in its hands, the stakes extend far beyond alimony or property exchange. These fertility-related assets challenge our traditional ideas of family, consent, and identity. While current legal frameworks favour mutual consent and the right not to parent, this often leaves one party bereft of future biological parenthood, prompting questions that law alone cannot completely answer.

Navigating such circumstances demands not only legal guidance but emotional resilience and profound ethical clarity. As society continues to redefine both family and autonomy, these conversations will become more crucial—and more challenging—for all involved.